Smart cities: Challenges on the path to better living - Part 2

Photo by Johan Mouchet on Unsplash

Although there are indicators that smart cities, underpinned by innovative technologies, have managed to revolutionize the lives of citizens, doubts around their efficiency in the context of privacy of personal data still arise.

After four years of preparation and debate, the EU Parliament enforced GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) in 2018, designed to harmonize privacy laws across Europe.[1] The regulation was put in action after it was acknowledged that there was an underdeveloped cybersecurity plan operating at a local level and that the handling of data by administrations was potentially problematic. [2]

The privacy issue typically revolves around education and transparency and opens a debate on what data is being collected, how it’s being monitored, how it’s being used, to whom it’s being sold, and what will be done with it in the future. [4]

One example of data-collecting procedures is the case of Antwerp, Belgium, where data on water consumption are stored by a private company, which signed a contract with the city. [3]

Furthermore, smart cities include certain types of surveillance technics which include strategically placed cameras across smart cities. This helps the city fight crimes at night and also determine the culprits who have committed crimes in public. Facial recognition is also a rising field, which tends to be implemented on a wide scale in order to make the place safer by identifying offenders the moment they are picked up by a camera. These types of measures are expected to reduce the number of accidents in a smart city.[4]

Although privacy issues in the era of smart cities are frequently discussed as problematic in certain circles, facts show that, in some CESEE cities, surveillance seems to be, simply put, a burning necessity.

Just recently, in the capital of North Macedonia, a country persistently rejected for EU membership, nearly all newly-purchased trach containers placed on multiple locations in the city were systematically destroyed by an unidentified group of vandals. The trash containers were a donation by the city’s municipality and their cost was a total of EUR 1500 each. [5] Most certainly, there are a number of similar examples of vandalism that frequently occur in many, if not most CESEE cities.

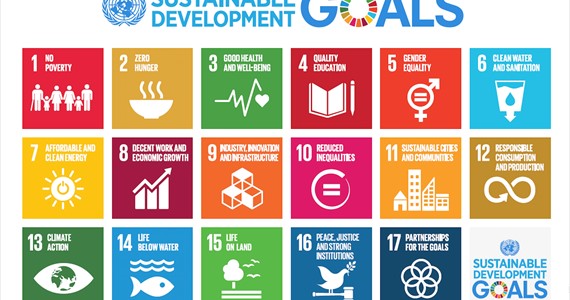

Quite often, objects of cultural and natural heritage are vandalized as well, and in that context, the UN's aim to protect and safeguard them in accordance with SDG11 can be secured by the implementation of technology which is common in ‘smart cities’.

Related Posts:

Benefit companies vs B-Corp: an Italian legal form toward sustainability

laian Three years have passed since the establishment in Italy of the Benefit Company (i.e., Società Benefit) with the 2016 Stability Law, the Italian counterpart of the so-called benefit corporations, better known as B-corp.

Sustainability in the hearts of Italians. Sustainable mindset

Over the years the concept of sustainability has become more and more conscious in the hearts of Italians, so much so that, nowadays, communities change lifestyles and are increasingly concerned about environmental conditions, issues such as pollution and of social problems.

When will animal cruelty go out of fashion?

Every year, more than 150 billion animals are slaughtered, ending their extremely short lives having endured unspeakable suffering under barbaric factory-farming conditions, to satisfy insatiable human appetites for food and clothing.

Tackling the refugee crisis: a business opportunity

The message is clear: tackling the refugee crisis is not only a corporate social responsibility, but also a significant business opportunity.

Digitalization: Challenges on the path to a better living

Digitalization refers to the way in which many domains of social life are restructured around digital communication and media infrastructures.

Smart cities: Challenges on the path to better living - Part 1

Making use of digital technologies in the fullest form possible is the core of the “smart city” concept.

EU Financing for SME Development in Latvia

The EC has identified the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) as one of its priorities, with a significant share of funding for this purpose.

From aspiration to operation: impressions from the NAEM Impact Conference

The NAEM is a professional association that empowers corporate leaders to advance environmental stewardship, create safe and healthy workplaces and promote global sustainability. It’s a great and welcoming community of passionate and committed experts.

Materiality of ESG issues takes center stage at US congress

10th July 2019 marked the first ever congressional hearing on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues in the United States.

EU Green Taxonomy and NFR Directive update: key takeaways

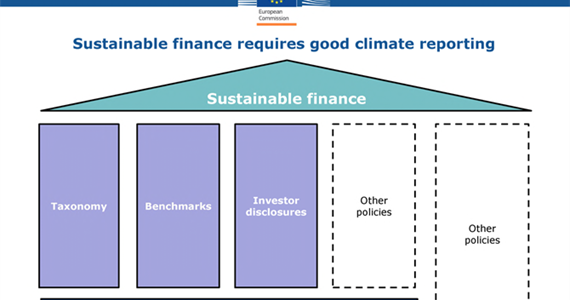

June 2019 has been a hot month for policy making around sustainable finance. The EU Technical Expert Group (TEG) published four pivotal reports for the implementation of the EU Commission Action Plan on Sustainable Finance

Interview with TBoxChain: a blockchain-based system to certify online reviews thanks to two key proves: Proof of location e Proof of identity

TBoxChain, a young start-up that has developed a new method to unmask false reviews of online consumers.

The teacher and the “bibliomotocarro” ape put wheels on books

The cultural project “to the limits”: an interesting example on how to spread culture within the small communities.

Who is Antonio La Cava?

SDG8: Economic growth for sustainable future

Although the number of workers living in extreme poverty is showing a substantial decline over the past 25 years, and the middle class now makes up more than 34 percent of total employment, the world economy is still facing serious challenges ahead.

Initiatives and obstacles to reaching SDG4

Every single country in the world is challenged to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. One of those goals, SDG4, is concerned with education policy issues which are not part of the international development agenda, but are of great value to the OECD member and partner countries.

Sustainable finance: Making Finance a critical element of Sustainability

As part of Sustainable Finance Action Plan, in June 2019 the European Commission by the Technical Expert Group (TEG) on sustainable finance has published three important reports including updated non-binding guidelines on corporate climate-related information reporting:

Developing small and family businesses to combat poverty

Historically, small and family businesses from generations have been inherited by the oldest EU member States. The opposite for most of the new Member States, this experience was completely destroyed during the Soviet Union.

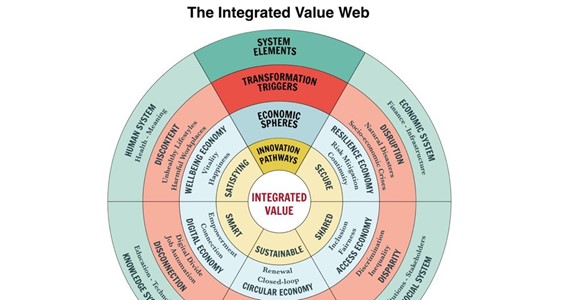

Just because it’s innovative, doesn’t make it good: The integrated value test for meaningful innovation

We live in a global economy where innovation is happening at an unprecedented rate and scale. According to the World Intellectual Property Organization’s 2018 report, patent filings for 2017 reached 3.17 million globally.

Latvia is the third poorest country in the European Union

In the field of anti-poverty policy, Latvia is the third poorest and most marginalized country, with a dramatic increase in the gap between the poor and the rich in recent years.

New EU electronic certification system will improve food traceability

According to the 2000 White Paper on Food Safety the ability to trace and authenticate food products throughout the food chain is a key issue for the EU food industry so in 2002 General Food Law made traceability compulsory for all food and feed businesses.

Are bike lanes are as sustainable as they seem?

In the Strong Towns podcast, “Are Bike Lanes White Lanes,” speaker and author of the book “Bike Lanes are White Lanes,” Melody Hoffmann identifies a critical urban design problem in bike lane infrastructure—addressing in-depth how bike lanes are not as “sustainable” as they seem, and can often deepen issues of classism, racism, and displacement.

Thinking about flight shaming, ethical travel and consumption options

So it seems traveling by train for longer distances takes around 10x longer than flight but is around 10x less carbon intensive. So yes, traveling by train can be a good choice for activists like Greta Thunberg, but also for regular people. But in another article I read that Greta Thunberg wants to avoid flying to the US and travel by a boat.

How can complexity science improve education?

One frequent mistake in social innovations and education, is to assume one-fits-all approach to solving social problems. We need to realize that managing in complex systems requires radically different tools than managing in complicated systems or chaotic systems.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

SDG3 not only aims to reduce major epidemics of communicable and non-communicable diseases, it also focuses on fighting the behavioural health risks such as alcohol and tobacco addiction, environmental issues like air and water pollution, as well as traffic accidents.

Towards a more humane and relevant education

This is a second article discussing difference between complicated, complex and chaotic systems, with possible implications for education.

Millennials are driving interest in sustainable investment

Sustainable, socially responsible or ESG (environmental, social and governance) investing is on the rise. A recent survey from Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing has found that millennials are leading the way with nearly nine in ten (86%) of them being interested in sustainable investing.

Sustainable infrastructure for better well-being

To reduce carbon emissions and air pollution, Mexico City constructed a hospital building that eats the city’s smog called the Manual Gea Gonzalez Hospital.

How can Slovakia contribute to global prosperity after #AllForJan?

Slovakia is a relatively young country, still in its twenties. For most of our recent history since the late 1990s we prided ourselves in being a “Tatra Tiger”, a fast growing emerging economy with a strong manufacturing base (think Volkswagen) and highly skilled and productive workers at business process offshoring centers (think Accenture).

Interview with Andrea Casadio, the creator of AllerGenio

How to help people who are affected by allergies and food intolerance?

A search engine can identify allergens in a database of more than eighteen thousand ingredients, scientifically validated by the laboratory of Human Health Sciences, University of Florence: this is AllerGenio , online platform which is a great help for allergic and intolerant people , since it recognizes the substances to be avoided in food.

A hymn to transformational change: four key takeaways from GreenBiz 19

“If we want things to stay the same, we need things to change”. GreenBiz 19 (Phoenix, 26-28 February) Joel Makower, GreenBiz Chairman & Executive Editor kicked off the event by quoting The Leopard, an Italian novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa.

Opinion: Non-financial Reporting Directive Update: What Is Changing?

The EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) is about to change. Surprised? You should not be. The EU Action Plan last year and the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance report this January were already discussing the update of the Non-Binding Guidelines (NBG) of the Directive.

Sustainability Made in Germany: Finance behind #DNP11

Hollywood has the Oscars and sustainability has the Deutscher Nachhaltigkeitspreis 2018 (German Sustainability Awards, #DNP11). The finance sector places a special role in financing decarbonization and all developments towards a sustainable future.

Social Enterprise: No Borders to Changemaking

“Social entrepreneurs are not just content to give a fish or teach how to fish. They will not rest until they have revolutionised the teaching industry” – Bill Drayton, Founder, Ashoka

Healthy Nutrition and Organic Food

The consumption of organic food has been increasing as part of rising consciousness and concerns of people on healthy living and nutrition.

SDG3 Health and Wellbeing: Improving mental health in the Republic of Croatia as a contribution to the UN SDG3

On October 10, 2019, on the World Mental Health Day, the Life Line Association organizes a Gala Evening and a concert to raise awareness about the problem of suicide and depression in the Republic of Croatia. The World Federation for Mental Health (WFMH) decided this year's World Mental Health Day to focus specifically on the topic of suicide prevention.

Celebrating 8th of March as an Official Public Holiday

Early this year, the state of Berlin has declared 8th of March to be an official public holiday to honor International Women’s Day.

The Importance and Benefits of Employee Health for Companies

In recent years, obesity and overweight became a prominent problem. According to the 2018 World Health Organisation report, more than 1.9 billion adults were overweight and 650 million were obese in 2016.

Heifer Foundation approach and examples of success in the Baltic States

Heifer Foundation is an international charitable organization with head office in Arkansas, founded 65 years ago by the American farmer Dan Vest.

You are What You Eat and Why Do You Eat?

The idea that you are what you eat has been a prevailing belief in many cultures throughout the history. For example, the ancient Aztecs would eat the brain of their rivals because they believed it gave them the wisdom and knowledge of the enemy.

Assuming global responsibility by closing all the loops

Closing all the loops is a very similar idea of assuming global responsibility – for the whole of our actions but also for people in faraway places. Closing all the loops thus shall be also an integral part of Agenda 2030 and applies to various Sustainable Development Goals, beyond the SDG12 of Responsible Consumption.

Is there poverty in Europe?

If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich. - John F. Kennedy

ASSOCIAZIONE RiSvolta – The Colors of Rights

The RiSvolta Association is a non profit social promotion association that aims to build a society in which human and civil rights are recognized, promoted and guaranteed for all citizens, without discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or any other personal and social condition, in line with what is established by Article 3 of the Italian Constitution.

Barilla aim to sustainability and entry to Bio market

After the launch in the marketplace of USA and other Europeans Country in 2016 of “durum-wheat semolina’s pasta from biological agricolture” signed by Barilla, the new proposal is coming in 2017 also on the shelves of Italian’s supermarket.

Sustainable modes of city

Creating an intelligent human society enables the development of sustainable cities in terms of environmental protection and economic and technological development. Sustainable cities rely on the digital city infrastructure to build intelligent buildings, transport systems, schools, and businesses.

Risk less as you go sustainable

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has gained a growing importance, during the last years, among academics, managers and citizens and its impact on firm’s performance is the center of several debates worldwide. As a matter of fact, according to the majority of CEOs worldwide, CSR is considered an “important” or “very important” task for their firms (UN Global Compact-Accenture).

Towards Sharing Economy: Joy of a shared toy

With each passing day, the world is more and more convinced that the economy system we are used to living in, is not sustainable. Climate change and resource depletion, followed by enormous consumption are some of the main problems that the world is facing nowadays. But now, more than ever, there is an emergence of companies that are moving further away from this way of doing business and might have a solution for these problems. Those companies are the main representatives of sharing economy.

7 CSR Trends that will dominate 2019

2019 will be a promising year of corporate citizenry and impact. Reporting, Community engagement, employee training, betterment campaigns and market feedback are all aligning to support a higher level of CSR activity than ever before.

How poverty started in USA and Why is poverty higher in the U.S. than in other countries?

Poverty is a state of deprivation, lacking the usual or socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions. The most common measure of poverty in the U.S. is the "poverty threshold" set by the U.S. government.

The Collettivo Donne Matera

The goal of the Collettivo is to contribute to the creation of a society that is as fair and inclusive as possible where social support, public health and education services, economic resources and employment opportunities can be guaranteed and adequate to a dignified life for all.

SDG 1 (No poverty) implementation in Latvia 2018

In the medium term, Latvia has prioritised reducing the poverty rate for employed persons and families with children, while continuing to improve conditions for older persons and per- sons with disabilities.

Social Development Goals in Everyday Contexts

In everyday activities of organizations from public and private sectors Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Impact as a concept are becoming even more important.

There are results in SDG action!

The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018 provides insight of the progress in the third year of implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Slovak SDG Priorities

On 13 November we at the Pontis Foundation organized our annual CEE CSR Summit in Bratislava and also held a discussion roundtable on SDGs.

SociSDG became official supporter of Global Survey

Global Survey is a project that picks up on expectations and oppinions on matter of sustainability, including the UN Sustainabile Developement Goals, in as many conutries as possible throughout the world.

Getting to know “Il Sicomoro”, a Social Cooperative in Matera

“Il Sicomoro” is the Italian translation of the sycamore, which looks like a fig tree and it is very popular in the Middle East. It is a common “character” along the streets in Palestine, where it leaves splashes of colour on those biblical landscapes, apparently very similar to the ones in our Lucania.

Well-being in our cities or why children need to play in the streets

World health Organization (WHO) lists road injuries and deaths as one of the top causes for people deaths. Moreover, that is a number one cause for male teenagers.

Why do we need global education?

How can companies, think-tanks and municipalities contribute to a more secure, sustainable and equal world?

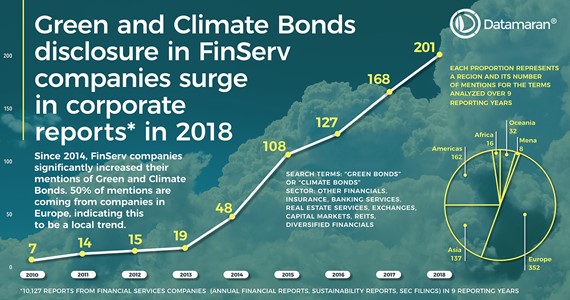

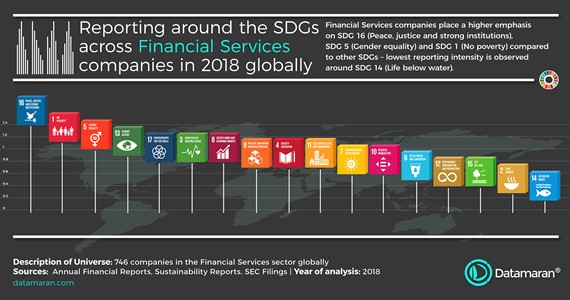

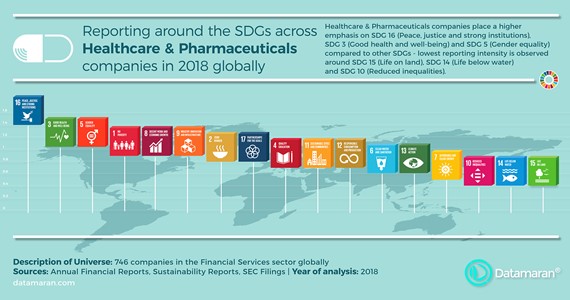

InfoBlog - Research: SDGs in the Financial Services sector

Datamaran started a dedicated project on monitoring corporate awareness on the SDGs across different sectors.

InfoBlog - Research: SDGs in Healthcare and Pharmaceuticals sector

After first Info Blog on the SDGs in Financial Services, Datamaran is following up with the results for the Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals sector.

What would happen, if there would be no poverty in the world?

Around 2,5 billions humans are living in poverty around the globe, mainly they are living in regions like Africa, South America and middle Asia. What would happens, if there would be zero poverty in the world?

A leader for change: What makes a sustainability leader?

In our journey towards exploring the UN Sustainable Development Goals we have travelled and seen some great examples of leadership. While our focus remains on SDG’s we have also explored good examples that has touched us, inspired and taught us.

Want to help UN SGD implementation and a give your contribution? Check My World 2030!

My world 2030 is a communication channel and a world wide citizen survey that brings people’s voices into debates about Sustainable Development Goals.

A month ago, young German photographers promoted sustainable development goals at the German Federal Government open day in Berlin

With over 20 000 visitors, themes like sustainable consumption, human rights, mental health and equal opportunities were presented through photo media by the young photographers.

SDG Leadership – A Tribute to Kofi Annan

The recent death of Kofi Annan gives me pause to think about the nature of leadership – and especially what makes one leader stand out, as Annan clearly did.

SDG5 Gender Equality: a Good Example of a Female Migrant Entrepreneur Employing Almost 150 Italians

The SDG5 "Gender equality" aims to eliminate all forms of discrimination and female violence, especially in the working sector where women aiming to open a business still face social and educational barriers.

Sustainable Cooking

When talking about SDG2, we always talk about how to prevent world hunger and what can be done to save people from it. We talk about ways of helping people who don't have enough to eat and improving the access of all people to a healthy diet, but we rarely speak about one way that can also have a positive impact on ending hunger – sustainable cooking.

Modern Slavery - the Other Side of Modern Society

As it may seem unthinkable, however, there are about 46 million people enslaved in the world right now. Modern slavery exists along all the prosperity and progress that is happening.

Impact of Climate Changes on World Hunger

People impact on climate and cause climate changes, and climate changes impact on people. What do climate changes have to do with world hunger? More than one could imagine.

Generation 3.0 - Changing education through prize competitions and bottom-up innovations

At Pontis Foundation we thought about how to support the topic of 21st century skills and improve learning outcomes of the next generation of people born into our relatively young and independent country of Slovakia.

The Circular Economy: A New Syndustrial Revolution

In a previous Soci-SDG blog (Closing the Loop: A Key Business Model for SDG 12), I wrote about the world’s first feature length documentary film on the circular economy, which I co-produced and presented.

That’s Absurd! The “Assurd” risto-pub experience with sustainability

On average, income inequality increased by 11 per cent in developing countries between 1990 and 2010.

Disability is referenced in various parts of the SDGs and specifically in those related to growth and employment, education, inequality, accessibility of human settlements, as well as data collection and monitoring of the SDGs.

Yves Rocher Fondation, commitment for the Planet

In the last few decades, increasing attention has been given to the topics of environmental safeguard and sustainability by the community. Within such scenario, the Yves Rocher Fondation promotes initiatives...

Economic and environmental sustainability: utopia or reality?

Does it really pay to be green? Is it possible to be both economically and environmentally sustainable? How important is the green technological shock?

The Conad sustainability challenge

Conad, the colossal of large retailers, has joined the Ecologistico2 program, devised by ECR Italia, the association that regroups the main production and distribution companies to improve the processes and efficiency of the supply chain, from the producer to the consumer.

How to reduce the use of plastic and is it possible to live without the plastics?

3rd of July is day without the plastics. As you may know, plastic bags and certain types of plastic containers are an enormous issue for the good health of our Ocean and seas and for environment overall.

Community of people to share ideas and projects

Among the trends related to sustainability that have been proliferating in the last years, certainly the shared creative spaces stand out. One of these is “Casa Netural”, a house in Matera in southern Italy, hosting people from all around the world...

SDGs Integration: How to Do It Right?

Current tendency towards sustainability promotes versatile ways for responsibility and integration of SDGs into business models, organizational culture, policy making, urban planning and spatial development...

Inspiring practices as guidelines for achieving SDG

As global challenges are getting more and more appealing, the need for facing them with responsible and innovative solutions is getting more demanded. As global challenges are always nested in particular local context...

Hydroponics, a way to achieve sustainable intensification

What does the future of food production look like? What are the increasing and increasingly urbanised people of the world going to eat in 2030? Do we need to destroy more forest hectares to accommodate the nutrition needs of billions more to come?

The UAE: From Fossil Fuel Present To Zero Carbon Future

"I do not want to bring the Bedouin to civilization, but I want to bring civilization to the Bedouin." - Sheikh Zayed

How to increase our social impact exponentially?

Everyone wants to leave a legacy and contribute to something meaningful. Many companies, non-profit organizations, donors or whole countries are asking how to measure social impact and increase it considerably?

Bike Messengers in the Mountains: The Sustainable Reality of 'Biciclò'

In the last years the bike messengers started to ride ever stronger. Even in Italy the phenomenon of bicycle couriers has spread out on a large scale and today over thirty exist at national level. In Potenza, Basilicata (a small region of Southern...

How is Podravka implementing the Sustainable Development Goals?

Podravka Group is one of the leading food companies in Southeast, Central and Eastern Europe. Thanks to the faith of their consumers, Podravka has become the number one food brand throughout the region.

The Decades Long Quest for a Digital Aristotle

Aristotle was probably the best tutor in the world and the most knowledgeable person of his times. But still his student, Alexander the Great, went on to conquer half of the world. Being smart it seems, doesn’t automatically translate into being...

SDG 2: Sustainable Food Production

Agriculture’s enormous energy consumption is related not only to food production, but also in large part to food distribution. The environmental benefits of organic food production can be lost if the food is constantly being transported thousands of miles to reach consumers. Buying local seasonal food can be an...

Collaboration for the SDGs

Monitoring and encouragement of SDG practices at European level is a challenge, as it is both international and national level activity. The alliance SDG Watch Europe has a goal to hold governments and the EU to account for the implementation of the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. It consists of...

The Sustainable Economy Is a Donut!

The objective number 12 of the Sustainable Development Goals aims to ensure sustainable patterns of consumption and production. Why is this an indispensable requirement for sustainable development? Because it is estimated that the world population will reach 9.6 billion by 2050, with this figure we would need the...

Closing the Loop: A Key Business Model for SDG 12

"Unless we go to Circular it's game over for the planet; it's game over for society." These are the opening words of the world’s first feature-length documentary film on the circular economy, called Closing the Loop, due for public release on Earth...

'Microcredit' to Serve the Sustainable Development

Since 2001, the Italian Banking Association has undertaken an in-depth study on the subject of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and its strategic importance within the modern banking business model. Consequently, in recent years an...

EU Commission Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth: Summary

About one month ago the EU Commission published the Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth, a dense 20 page document that "sets out an EU strategy for sustainable finance" building upon the Final Report of the High-Level Expert...

The Need to Innovate Beauty Industry

Have you ever thought of the highly underestimated cost we pay for everything we consume? And I am not talking here about the price we pay for solely acquiring goods. What I have in mind is slightly more overlooked and all-encompassing, which is each product's afterlife cost, e.g. the amount of resources it takes to...

How to Bring Prosperity to Smaller Town and Rural Areas?

Half of global population already lives in cities. However, we witness the widening differences between ever more prosperous large cities, that are winners of globalization, and the rest – small towns and rural areas that are often...

The Pioneering Change Agents of Berlin: Post-Berlin Reflections

My first impression of Berlin, as I got out of the airport’s bus shuttle and entered the metro station, was the cold February breeze and the wealth of street art. I was here for a week of learning on sustainability with colleagues and partners from...

The Future of Sustainable Finance

Last week I attended the London meeting of the The Future of Sustainable Finance at the G7. The panel of knowledgeable experts provided a fascinating discussion. It touched on many of the areas raised in the detailed 2018 report by the EU’s High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. For financial institutions, the report...

Are Sustainable Development Goals Material?

The SDGs already achieved the significant work of creating a common platform of targets and indicators shared across governments, institutions, academia, investors, media, and business. And this is not rhetoric. In the past few months, I’ve been in several conversations with business, academia, and investors concerning...

Can We Make Zero Poverty World or Not?

Despite the on-trend rhetoric and optimism, the chances of (all but) ending absolute poverty in our generation are slim. The chances of ending poverty altogether are zero. The closer we get to ending extreme poverty, the harder it is going to be to do it. We're going to have to pretty much end violent conflict...

Achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals with European Projects

From 25 to 27 September 2015 in New York, during the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit the document Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was drafted by the Heads of State. It...

Bringing About the Desired Future: The Value of SDGs

Many people feel that we live in very uncertain times. The world is changing too quickly. We hear about the threats of automatization and artificial intelligence that might replace even the jobs of radiologists and bankers. We witness the...

SDGs for the Generation Z

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals were adopted in 2015 as the universal call to action to end poverty and hunger, protect the planet and ensure inclusion, peace and prosperity for all by 2030. Agenda 2030 is playing a very important role in shaping tomorrow’s living conditions. However, without active individual...

Why Is It so Hard for Many People to Get out of Poverty?

Poverty is about a lack of money, but also about a lack of hope. People living in poverty often feel powerless to change their situation. They can feel isolated from their community. If you want to overcome poverty, you need a combination of...

Global Targets & National Responsibility? German Sustainable Development Strategy

In September 2015, world leaders gathered in New York adopted a global agenda for sustainable development – the 2030 Agenda. In Paris in December 2015, they reached a follow-up agreement on international climate protection. Germany...

Global Festival of Action for Sustainable Development to Be Held in Bonn, Germany

The Global Festival of Action for Sustainable Development is powered by the UN SDG Action Campaign with the support of Germany's Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. The Festival will focus on three core...

Focus on Sustainable Cities and Communities

Cities have often been a vehicle for generating new ideas, commerce, culture, science, productivity and social development, and up to the present they have also enabled people to improve their social and economic conditions. However, many challenges persist to keep city centres as places not dangerous for both lands...

The SDGs and Business: New Horizon or New Smokescreen?

The 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by 193 countries in September 2017, are very fashionable now – especially among big companies. But are they really changing the way that business does business? Or are they little...

Orange Is the New Green: From Citrus 'Pastazzo' to Catwalks

The idea of Adriana Santanocito and Enrica Arena, founders of Orange Fiber, answers the new innovation and sustainability needs of the fashion industry: Orange Fiber is in fact an Italian start-up which develops sustainable...

Sustainable Consumption and Recycling of Products in Transport Industry

Based on data from the Paris Conference on Climate Change, transport is responsible for 23% of global indirect emissions. New initiatives for improving urban transport and accelerating the deployment of electric vehicles have been...

Changing Mobility Habits for a Healthier Life

Contributing to the third Sustainable Development Goal capital city of Lithuania is creating a sustainable urban mobility plan (SUMP) for its inhabitants. SUMP has to encompass various mobility modes and variations and one of the themes of the city strategy is to plan how to change people’s behaviour in mobility...

Sustainable Cities and Communities: Lessons from Madagascar, Ecuador, Singapore and the UK

SDG 11 calls for making cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. But why do sustainable cities matter? This is the topic a group of researchers will be...

Food and the Sustainable Development Goals

Food and agriculture feature prominently in many of the Sustainable Development Goals, because they are interconnected with almost all aspects of economy, environment and society, from hunger, malnutrition, desertification, sustainable water use, loss of biodiversity, to overconsumption, obesity and...